Material Dialogues: Reflection, Chance and Perception in Expanded Painting

In the last year, my experience in art has shifted from a desire to control to a more open conversation with the material. This transition is a result of an increasing interest in the notion that materials have agency of their own, which can influence, resist, or modify the process of designing. In my recent experiment with reflective and translucent materials like resin, acrylic and mirror film, I have started to notice how light behaves otherwise. These visual events generate shifting relations between the artwork, the surroundings and the spectator. Painting can no longer be thought of as a static two-dimensional surface, but instead as an ecological system determined by reflection, serendipity and perception. Meaning is generated in the transmogrification of light, transparency and dimensional uncertainty.

My current practice is underpinned by Herbert Molderings’ reading of Marcel Duchamp’s aesthetics of chance as an ‘experimental condition of art’, negotiating a balance of control and accident, and letting material behaviour intervene in making. I enjoy using carved acrylic with resin pigment since the unplanned optical effects of refraction, diffusion, and reflection often become a central component of the image’s logic. My research also adopts Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s idea of embodied perception as well as the work of Michael Petry and Mark Titmarsh, who shift the field of painting through reflections on materiality and spatiality. In this sense, painting becomes less an object and more a relation: a field where light and matter enter into a perceptual exchange that is ecological in nature and that continually remakes the painting.

Through this essay, I try to investigate how material agency, spatial experience and the operation of chance might together reconfigure painting as an expanded, ecologically attuned practice. I aim to relate philosophical ideas about perception and materiality with practical experience through means of carving, resin embedding, layering and allowing light to take centre stage as it can blossom in unexpected ways.

Subsequently, the discussion will first ground reflections, perceptions, and chances in theory, before turning to various contemporary artwork that exemplifies these reflections, perceptions, or chances. It will end with a reflection on my own experiments, assessing how a conscious acceptance of uncertainty can enhance perceptual activity and reciprocity of relationships between viewer, space, and work.

Material Dialogues: Reflection and Spatial Ecology

Contemporary artists have redefined painting and sculpture by examining the relationships. No longer merely an optical effect, reflection is used to interrogate how viewers experience and inhabit space. Olafur Eliasson, Anish Kapoor, and Nicolas Deshayes, among other artists, stand out for offering material behaviours, environmental conditions and viewer participation as critical functions in perceptual systems wherein control and chance are indistinct.

Eliasson’s installations use light and space to discover perception, which makes reflection an active and changing experience instead of a finished visual effect. Installations like Your Spiral View (2002) and The Weather Project (2003) throw the visitors into spaces that react to their movement and occupancy. The initial visual and material impression of a work of art has a specific influence on its interpretation. Eliasson uses the exhibition space to create a situation where seeing is shared. Viewers do not see an image but become observers in a space of light and atmosphere that is constantly changing.

In contrast, Kapoor’s work – including Shooting into the Corner (2008–2009) and My Red Homeland (2003) – reflects on the inner workings of this issue. Disruption and unpredictability are frequent creative forces in his works as matter assumes form through processes like compression, accumulation or collapse. Kapoor does not strive for perfection or control of the materials. He lets them reveal their own energy and resistance. In this way each work becomes an evolving encounter of physical process and perception. As a result of this approach, the installations conjure a sensation of depth and movement, with form emerging through a negotiation between rule and accident.

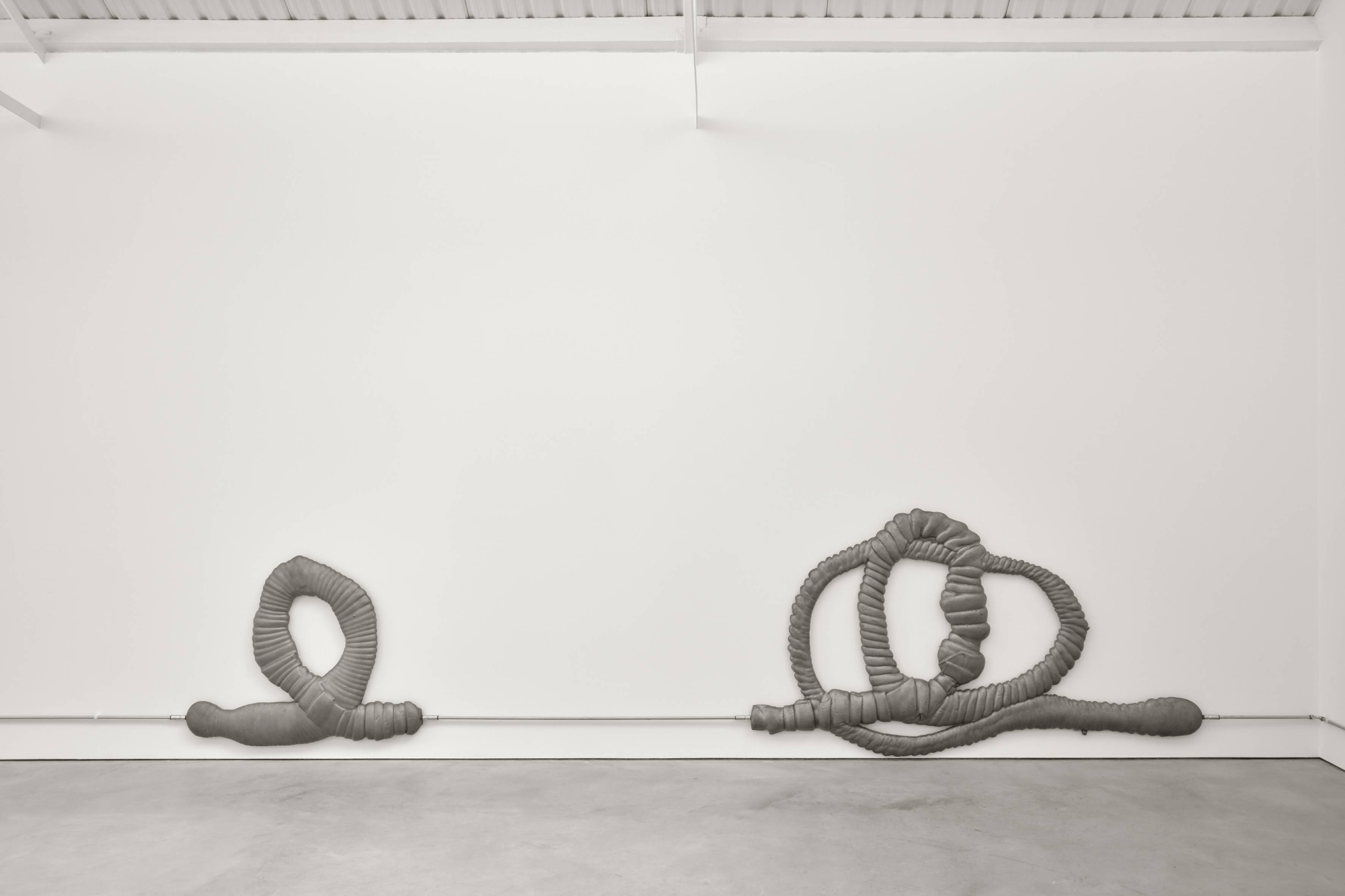

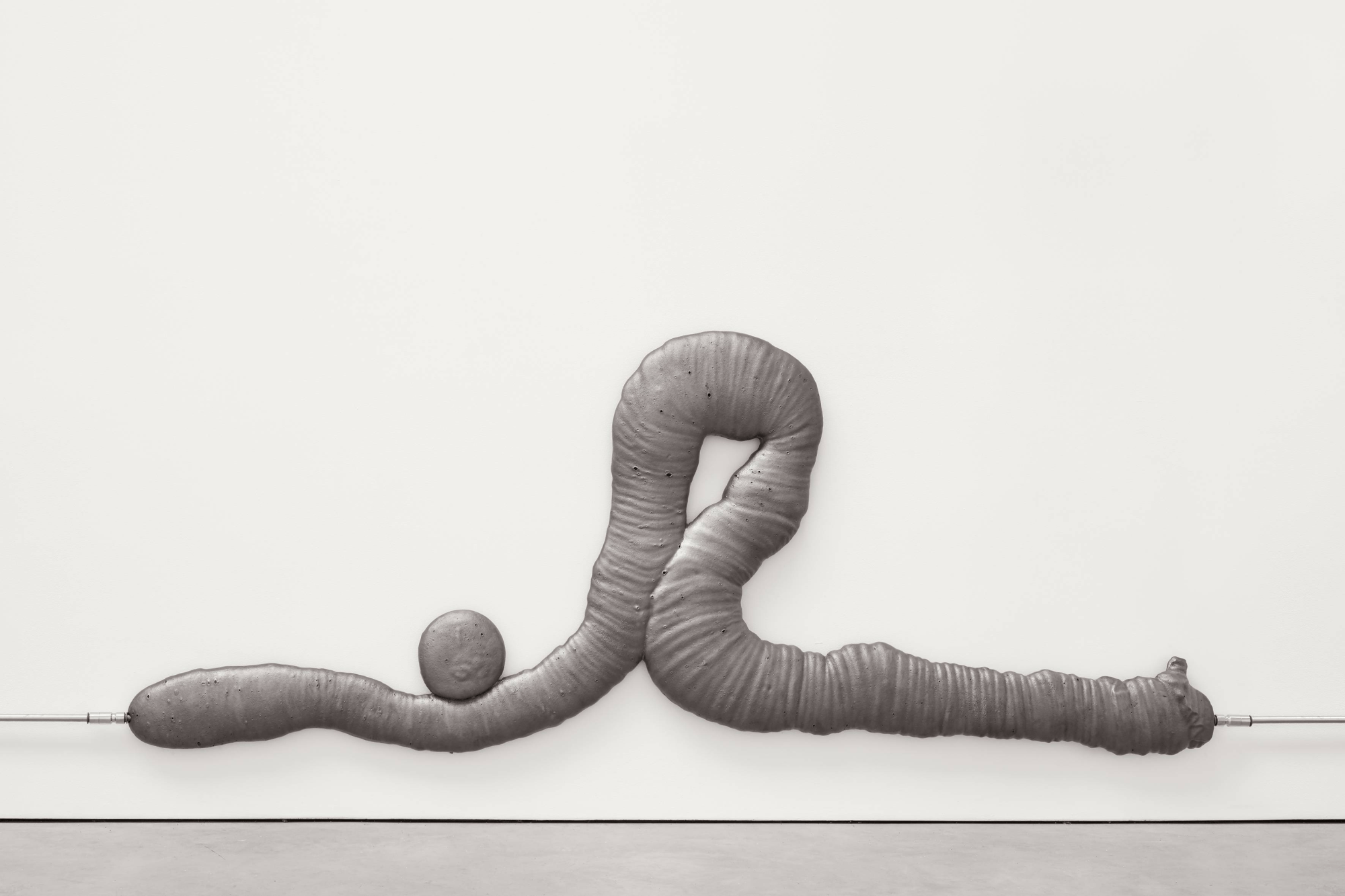

In a similar vein, Thames Water (2016) by Nicolas Deshayes also explores the relationship between order and chance. The artwork exhibits cast iron structures that twist and sag as though they’re living organs or plumbing systems. The surfaces of these objects which are created with ribbed shaping, appear to be burnt shapes due to the irregular cooling of molten metal. The opposing forms of these structures in fluidity and irregularity with the steel pipes that frame them is a striking one. It serves to show the tension between human precision and material autonomy. Deshayes’s sculptures are infused with life due to unseen systems; bodies and machines, which together make the functional, depend on the non-functional.

By reflection, material chance and physical process, these three artists’ circumstances put perception into action as an event ecological—a system of feedback involving matter, environment and consciousness. The artists’ works are sensitive to uncertainty and transformation and look to light, gravity and material behaviour to generate meaning rather than representation. Seeing perception as active and relational, and constructed, is the basis for my own practice, which aims to extend this idea into the expanded field of painting.

Olafur Eliasson — Reflection as an Ecological System

Olafur Eliasson’s work shows how reflection and transparency can turn perception into a living relational system. Instead of using light as a tool, he uses it as an active agent that creates relationships between the viewer, material and environment. For the installation The Weather Project (2003), Eliasson filled Tate Modern’s enormous Turbine Hall with fine mist and gently illuminated at one end by a semi-circle of hundreds of lamps. The “sun’s” mirrored ceiling closed the circle, creating a dappled light effect throughout the entire space. Visitors lie down on the floor to observe their reflection in the ceiling artwork. As human presence impacted this work, it no longer became a static image but rather a social and perceptual event.

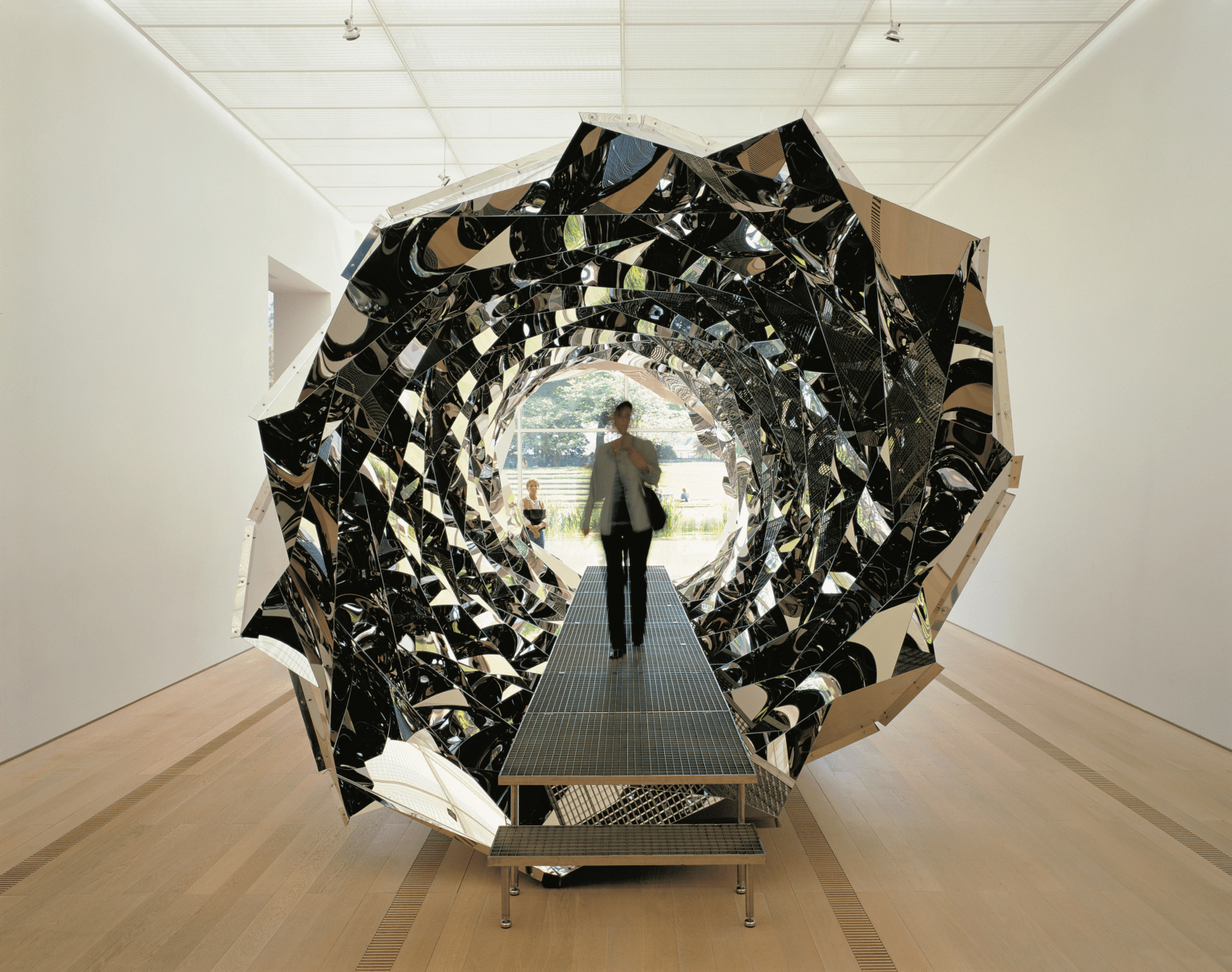

In Your Spiral View (2002), Eliasson makes reflection a spatial experience. The work involves a tunnel comprising a series of triangular segments made of mirrors that twist in a sequence. The inside of the tunnel is kaleidoscopic, which contains space and also expands it. As people walk through, their reflections are broken up into many pieces, folding the surrounding environment. The corridor seems to breathe with moving light as every step you take changes how you perceive time. Instead of simply projecting a static image, Your Spiral View sets up a scenario whereby the viewer’s body becomes included in the material process. Eliasson’s consanguineous exchange of movement, light and form transforms reflection from being a visual tool to a living building that tests how perception and space co-evolve.

In these two installations, reflection functions as a form of participation. The audience’s movement, gestures, and silhouettes actively shape the visual experience, embodying what Bishop describes as installation art’s defining quality—its insistence on the viewer’s literal presence. Bishop notes that installation art “creates a situation into which the viewer physically enters” and “presupposes an embodied viewer whose senses of touch, smell and sound are as heightened as their sense of vision” (Bishop, 2005, pp. 6). Eliasson transforms light into a relational force that depends on the viewer’s physical and emotional engagement, turning perception itself into a collaborative event. His installations echo Merleau-Ponty’s notion of embodied perception — the idea that perception is not a detached act of observation but a mode of being-in-the-world, through which truth and experience are realised via the body’s engagement with its environment (Merleau-Ponty, 1945, pp. 11–12).

Eliasson’s work reshapes art, space, and the environment. His installations do not only occupy a given site but reconstruct it by turning the architectural interiors into a dynamic system of light, air and reflection. The Weather Project (2003) turned the Turbine Hall into an artificial space that mixed natural and built elements into one. In Your Spiral View 200,2, a simple corridor became an optical field that was dependent on the movement of the viewer. In Eliasson’s works, space is an evolving organism, unlike a fixed container. Atmospheric and spatial elements such as mist, temperature, and illumination are perceived to be materials. Eliasson reveals how the environment itself can become both medium and subject of contemporary art through this synthesis of architecture and atmosphere.

Anish Kapoor — Material Chance and the Transformation of the Body

Eliasson encourages us to explore perception through environmental immersion, while Anish Kapoor turns inward, finding something within material transformation and chance. Through his practice, physical processes such as accumulation, compression, and gravity come to form a part of his making. Shooting into the Corner (2008–2009) features a pneumatic cannon that fires repeated large balls of red wax into the corner of a white gallery space. Each impact generates random splats and deposits, creating an ever-evolving mass sculpture in its wake. According to the context, in this scenario, chance is not seen as a breach of artistic control. As Molderings (2010, p. 53) observes in his discussion of Duchamp’s aesthetics of chance, observes in his discussion of Duchamp’s aesthetics of chance, the “experimental condition of art” transforms accident into a method of discovery, where form and meaning arise through the interplay between intention and contingency. Kapoor’s work encapsulates this idea by producing the randomness of the physical act of making sculpture into an extended inquiry into perception, materiality and time.

Likewise, in My Red Homeland (2003) the deep red wax is formed into a great circular field. It is dense, visceral and mutable. The mechanism moves with an almost ritualistic repetition. It pushes the wax. It folds the wax. It compresses the wax. The wax resists the force from the mechanism. It will yield to the force from the mechanism. The mechanism works under varying conditions of temperature, density, and gravity. Even though it looks like the movement is mechanical, the outcome is never predictable. The sculpture rather goes through a cycle of accumulation and erosion. Moreover, this proves that the material has the capacity for self-determination.

This evolving process exemplifies what Titmarsh (2017, p. 27) identifies as painting’s movement beyond surface and frame, where material and spatial processes replace fixed representation. Kapoor’s My Red Homeland develops this idea in the temporal dimension: instead of a frozen painting, the picture field becomes a material event in unfolding time. The ongoing movement of the arm indicates that there’s an eternal return, through which the work recreates itself due to duration, friction and chance.

The observer is conscious of the material energy in the physical object, as well as the durations and rhythms of generation and decay, due to this incessant transformation. The presence of red wax,which appears like flesh, blood or rock, grounds the work in a bodily relationship with the world. My Red Homeland is not just a sculpture. It is more of a space that stages the tension between control and contingency. It raises questions about the limits of painting, sculpture, and time.

Here, Kapoor’s practice crystallises a core proposition of the essay: form is not fixed but continually negotiated between intention, mechanism, and matter. In Shooting into the Corner, impact and accumulation make chance legible; in My Red Homeland, slow rotation and resistance expose time as a shaping force. In both of these works, wax acts as a live substance that captures pressure, heat, gravity and duration so that repetition becomes variation and control becomes contingency. Thus, perception is staged as a process. The viewer does not merely look at an object, but witnesses an ongoing event in which meaning emerges from material behaviour.

The combination of the works blurs the distinction between painting vs sculpture, image vs environment. They replace representation with transformation and composition with choreography, and finish with becoming. Kapoor reveals that the “work” is less the final form than the conditions that allow matter to act—an ecology of process in which accident is not error but knowledge in motion. This paves the way for the next case, where industrial systems and organic irregularity continue to challenge the tension between order and chance.

Nicolas Deshayes – Form, System, and the Tension Between Control and Chance

The artwork Thames Water, 2016, made by Nicolas Deshayes, features a series of cast-iron bodies that undulate along the wall in ribbed segments, which bulge and constrict. The profiles kink and droop as if inflated from within; tight corrugations suggest a muscular, peristaltic feel. Seen in sequence, the forms oscillate between infrastructural tubing and soft anatomy—a hybrid radiator–intestine–duct. Their matte metal absorbs light, while edging catches a soft sheen that guides the eye across each lump, bend, and fold. Set against the straight runs of galvanised pipe—reads as conduits, as if carrying hot water—their wavy silhouettes stage a clear tension between engineered order and bodily irregularity, hinting at gravity, heat, and pressure without fixing the work to a single cause.

Below all this formal play is a quiet commentary on systems. The invisible stuff. The plumbing and circulation systems that the body and the city run on. Instead of explaining these systems, Deshayes projects their internal contradictions: the industrial becoming organic, the mechanical visceral.

Thames Water’s oscillation between order and chance is less the literal result of undisciplined forces than a condition produced for effect; an aesthetic of as-if. The bulbous, kinked and sagging profiles look like residues of flow and pressure but feel almost controlled and deliberate. They are seemingly calibrated alongside the straight galvanised runs that surround them. What Deshayes stresses is the perception of raw indeterminacy, not raw indeterminacy as such. A designed irregularity that mobilises the look and language of chance without surrendering authorship. The artwork provides an abstraction compared to the autonomous process of the growth of a tree. The forms invite one to witness contingency – to see plumbing becoming flesh – while remaining fixed in conscious decisions about rhythm, spacing, and scale. Instead of showing that randomness creates form, Thames Water shows how chance can be constructed and made legible. That is, where we might see unpredictability, structure, and control show themselves.

The combined works of Eliasson, Kapoor, and Deshayes show how reflection, chance and the agency of materials can allow artistic making to become an ecological and perceptual practice. All artists create through a balancing act of control and unpredictability, whether creating an engaging play of light in Eliasson’s installations, allowing visceral behaviour of matter in Kapoor’s wax works, or instilling an industrial organic tension in Deshayes’ cast-iron forms. Meaning does not come from representing something which already exists; rather, it unfolds in practice between materials, environments, and the viewer’s embodied perception.

My artistic research is greatly influenced by the way form and process relate. Through the use of materials such as resin, plaster, and acrylic, my challenge is to create conditions that activate endeavour and indirect dependence between perception and reality through effects of weightlessness, transparency, and reflection. In the following section, I will reflect on how these thoughts manifest within my practice, in which light and chance come together and shape spatial, ecological and sensory experience.

Practice Integration: Reflection, Material, and Contingency

I currently seek to make perception alive and happening through light, transparency and the behaviour of the material. I’m interested in the point at which control gives way to collaboration—when materials thrall begin to control things. My recent experiments have the resin, acrylic, plaster and reflective film acting not only as a support or a tool but as an active agent. I often use gravity, heat, and fluid movement to create unpredictable flows and interactions of colour. These processes are the equivalents of stunning pieces of light trapped in movement, thereby making chance part of the logic of the composition.

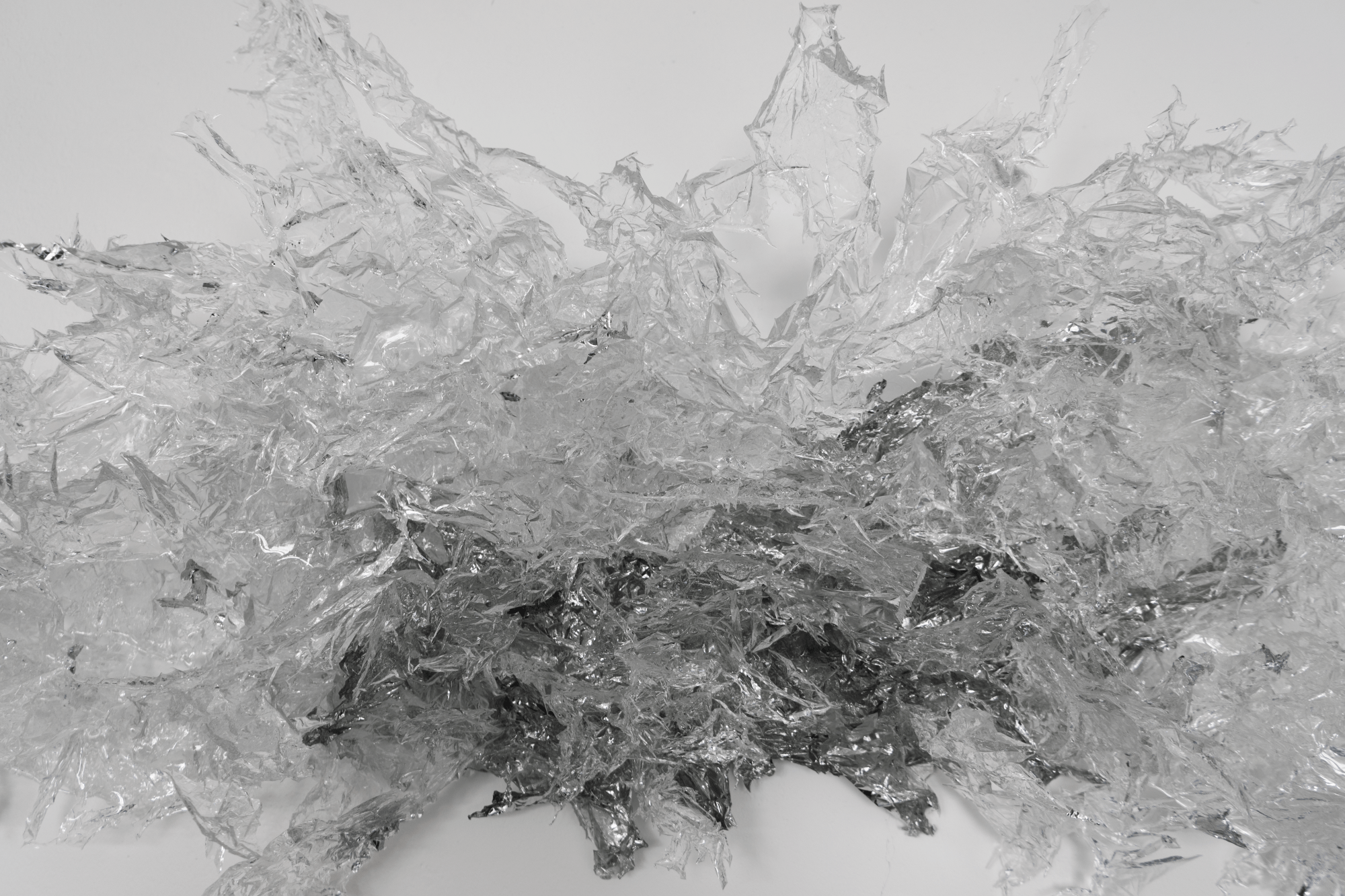

2025

95x43x15cm

Epoxy resin and Mylar film.

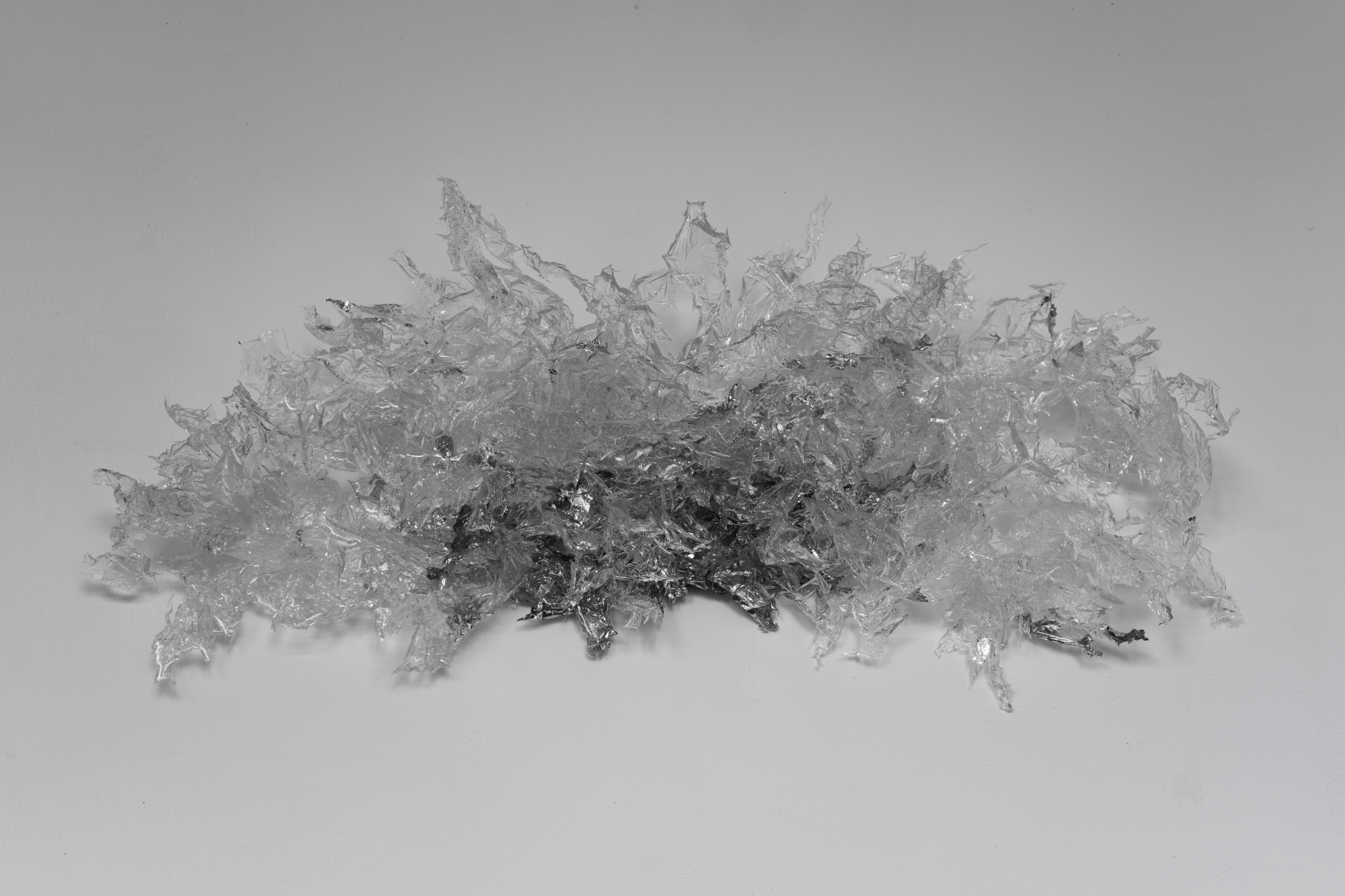

My MA show work, Crystalline Bloom (2025) is the clearest instance of this. This larger piece, which developed from Crystal Interweave, extends my work on transparency and reflection in depth. With multiple layers of resin and natural resin flow due to gravity, I can achieve a crystal-like structure that seems to grow out of the wall. This piece is installed with an invisible hanging system that causes it to float, weightless, between the solid surface and open air. The crystal-like pattern of the work refracts when the light penetrates its surface, creating a slow rhythm of change.

2025

95x43x15cm

Epoxy resin and Mylar film.

I’m not trying to make perfect, “crystal-clear” images. I want people to notice how their view changes as they move. A quiet room says a lot about simple things. Step a short distance and there the glare on the surface slides. Tilt your head and fine crack doubles up. Move your whole self a few more centimetres and the sharp edge turns soft. The transparent and reflective materials will make the picture do not stay still; you do. Your movement finishes the work. Since the materials are transparent and reflective, the image never settles—highlights slide, edges blur, and layers appear or disappear as you change position. Thin layers of resin catch and bend light, so the image never fully settles. Rather than providing you with solutions, the work, instead, slows you right down to enable you to test how space, light and material react. This slight wobbliness—the wobble of a reflection, or the drift of a shadow—invites us to see painting as an ongoing event, more a small environment than a picture.

2025

95x43x15cm

Epoxy resin and Mylar film.

With this in mind, I do not aim to represent an image. It’s not about bringing about seeing, but about creating the conditions through which seeing can unfold as an event in time. When light shines through resin, it animates the surface from inside the artwork, blurring the lines between painting, sculpture and installation. Every artwork is altered by the time of the day, the orientation and force of (natural or artificial) light to which it is subjected, the movement of the body in space. This lack of permanence does not signify a loss of control. According to this, artwork will not be stable but in a state of flux to allow relations. I want to create a moment when the material world we see is also that which we are looking at in ourselves; a moment when what we are looking at is not only optical, which is possible, but also looking at how gravity behaves accidentally, and transparency is fragile.

My work highlights how we co-exist with materials rather than just using them through such gestures. Like ecological systems depend on balance and responsiveness, my process relies on sensitivity to the chance and the transformative. The art, therefore, is not an object but an environment that gets constantly remade with the light, space, and humanity.

Conclusion

The essay depicts how ecology, transparency and chance operate in painting as a situated practice. Through Eliasson’s atmospheric spaces, Kapoor’s time-bound wax processes, and Deshayes’s tension between industrial order and organic irregularity, perception emerges not as passive viewing but as a live negotiation between light, matter, and bodies in space. My own practice operates according to this relational logic: materials are collaborators, not tools; gravity, refraction, and surface action help compose the work; and meaning comes from the movements of viewers and changing light. Instead of correcting images, I prefer to create situations in which the perception stays alive, the surface flickers, the edge softens, and the reflection slips. In this way, painting is less a thing than a changing environment: a field in which controlling power and contingency continually meet and where form is always becoming.

Bibliography

Bishop, C. (2005) Installation Art: A Critical History. London: Tate Publishing.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945) Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Colin Smith. London: Routledge.

Petry, M. (2011) Mirror Mirror: The Reflective Surface in Contemporary Art. London: Thames & Hudson.