I. Introduction: The Dance of Material Narratives.

The impact of this research unit on my art-making has been significant. I began focusing on the design possibilities existing between 2D and 3D objects, but am now concentrating more on the material itself. This change embodies not just a technical shift but a re-positioning in my identity as an artist, from a designer who ratifies everything to a collaborator who works together with materials.

I now value randomness and chance more during my creative process. I have noticed that whenever I have worked with materials like epoxy resin and Mylar film, the most brilliant artistic outcome seems to be an accident. While demolding “Tilted Time”, I saw cracks form. I was initially quite upset, but then it occurred to me that the cracks were actually quite expressive of the material itself. My findings made me wonder as an artist, do I have to have 100% control over the process, or can I let some of the creativity be dictated by the material?

I will discuss two critical subjects. First, how do I find the balance between letting go and controlling? This question deals with the dialectical relationship between material agency and artistic control. Second, the transformation process in my practice has evolved from controlling tightly to allowing release consciously. Furthermore, how has this affected my methods and finished works? I want to track my practice and the wider conversations in contemporary art on the subjects of material, control and chance through my work.

II. Materials as Collaborators: Conversation Not Conquest

The use of epoxy resin in my work has developed to such an extent that it has changed my identity as an artist, from a controller to a collaborator.

Establishing a “Collaborative Relationship” with Epoxy Resin

2024

60x60x0.4cm

Acrylic Sheet and

Epoxy Resin

The first new meeting I had with epoxy resin was “The Labyrinth”. While filling the grooves in acrylic boards with resin, I discovered a colourant that diffuses like no other, creating effects such as an ink drop in water. I found this technique by accident and explored it further, which intrigued me. I started to learn how to listen to the material’s voice through this experiment.

(Ingold, 2013, p.31) argues that “materials do not exist, in the manner of objects, as static entities with diagnostic attributes” but are rather “substances-in-becoming” that are “always and already on their ways to becoming something else.” Observing the way colours flowed and transformed inside resin showed me how “alive” this material is. I discovered that creating is not simply about imposing our wishes on a material. It is much more engaging and fun; we communicate with the material so that it can start creating with us, rather than creating using the material.

How Unexpected Cracks Transformed My Creative Approach

2025

60x60cm

Epoxy Resin

My connection to materials began to change through “Tilted Time.” At first, I thought that since the resin drying time is very slow, I could use this property to express the flow time. The base of the material I chose is acrylic board. Not adequately taking into account the acrylic’s demolding property and the resin’s toughness, the work broke during demolding. Although I was annoyed, this “failure” generated the basic shift in my approach.

I began to question: What else could these pieces do? Could they become new artworks? In this way, Ingold’s notion of “following materials” was enacted. (Ingold, 2010, p.92) argues that “making is not the imposition of form on matter but the discovery of the possible forms within the material itself.” This process requires the maker to “follow” the material, aligning their movements with the material’s properties and tendencies.

It freed me from the “create first, execute later” model for creation to open creation. The lines told the “life-history” of the material, the resin and the acrylic’s reaction. Instead of trying to control it, I learned to embrace it and work with it.

Traditional Control Versus Collaborative Approach

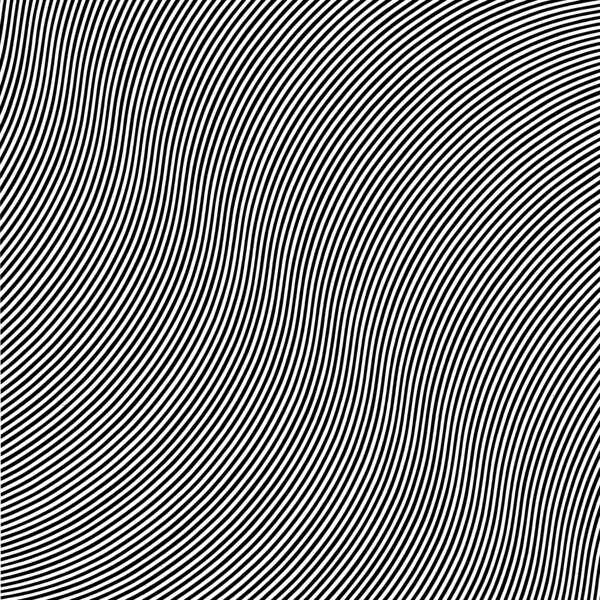

Bridget Riley, 1966

Emulsion on board

101.50 x 101.30 cm

Bridget Riley’s “Over” (1966) is an example of traditional artistic creation applying tight control of materials. Riley’s optical illusion works require absolutely precise execution, allowing no “accidents” or “autonomy” from the materials; each element must be precisely positioned to achieve the intended visual effect. In this creative mode, materials are viewed as passive carriers, completely subservient to the artist’s intentions and designs.

My approach is collaborative. (Ingold, 2013, p.69) describes the creation process as one where “the task of the maker is to bring the pieces into a sympathetic engagement with one another, so that they can begin – as I would say – to correspond.” I learnt to respect the resin’s will and let it flow freely.

(Ingold, 2010, p.94) describes the skilled practitioner’s relationship with materials as one where “the conduct of thought goes along with, and continually answers to, the fluxes and flows of the materials with which we work. These materials think in us, as we think through them.” When colours diffuse or imperfections occur upon demolding, I mentally create through materials, rather than about them. Materials’ agency interrupts anthropocentric assumptions in the making of art.

Material Agency Theory

This approach is in line with today’s views on material agency. Through Ingold’s framework, I have adopted an understanding of the material-artist relationship which resists the notion of the material as a passive tool. (Ingold, 2013, p.6) contrasts two approaches to making: “The theorist does his thinking in his head, and only then applies the forms of thought to the substance of the material world. The way of the craftsman, by contrast, is to allow knowledge to grow from the crucible of our practical and observational engagements with the beings and things around us.”

In my practice, resin is a partner that has its own properties. When it flows, when it diffuses colour, when it behaves unexpectedly with other materials, the material displays what Ingold refers to as its “life-history.” By respecting the material’s properties and collaborating with them, I have found richer possibilities than what a preordained execution could offer.

Thinking and doing are ultimately the same. When I work with resin, I think and do. Through this collaboration, my process and the meaning of my work have changed. It is no longer just a projection of my intentions, but a co-creation.

III. From Canvas Constraints to Material Freedom

My artistic journey reflects a liberation from traditional painting constraints toward material freedom, fundamentally altering both my formal approach and conceptual framework.

At first, I focused on creating textural brushstrokes on canvas and later experimented with expanding foam for dimensionality, yet remained confined by rectangular formats and precise colour application. As Staff notes, “Whilst a certain number of painters who had emerged out of a set of precedents that had first been espoused by Greenberg continued to develop, if not further entrench, their work according to what remained, for the most part, a formalist orthodoxy, others were more willing to open up, as it were, their respective practices to the currents that were emerging both within the discourses and the milieus of art” (Staff, 2013, p.63). Despite material experimentation, I continued operating within painting’s traditional conceptual boundaries.

Breaking free from the rectangular frame marked a pivotal moment in my practice. Once freed from these confines, I discovered materials could dictate their forms and relationships with space, allowing more organic integration with surroundings.

Journey of Transformation

The evolution from geometric to organic forms is visible in my work. “Mangrove Forest” remained constrained by rectangular formats and conventional techniques. My transitional works, “Mineral Dreamscape” and “The Labyrinth” incorporated three-dimensional elements while still anchored to rectangular supports.

My recent work, “Crystal Interweave” represents a radical departure, protruding from the wall and integrating with architectural space as if growing organically from the surface. This approach aligns with Staff’s observation that in contemporary practice, painting is “not a self-contained vehicle to be looked at, but a work to be seen in relation and aspect to the space it exists in” (Staff, 2013, p.155).

IV. Transformative Turning Points: A Critical Analysis

My artistic practice has changed quite a bit, and we can trace this change through four works. My journey from rigid control to material collaboration is told through these pieces that are the materialisation of an evolving understanding of material agency.

- The control and precision start from “Mangrove Forest”.

2022

41x51cm

Oil on Canvas

The referent of the “Mangrove Forest” bears the characteristics of my first works: precision of control over material and effects. For this piece, I mainly used modelling paste and oil paint. With a palette knife, I applied the modelling paste to the canvas with precision, creating elements of texture that I had decided upon in advance. I used brushes to apply the oil paints and mixed the colours to create my effects.

This piece represents my original way of making art, where materials just became tools for me to execute my ideas. The artwork stayed in a normal rectangle shape, and all the texture, colour and everything else was completely in my control. Materials, in this sense, have no agency. I made choices, and the materials were received according to my choices.

- “Mineral Dreamscape”: Limited Freedom Within Constraints

2024

110x110cm

Expanding Foam,

Chicken Wire, plaster and

Spray Paint.

My journey progressed with “Mineral Dreamscape,” where I began experimenting with more dimensional elements. I initially used chicken wire as a framework for expanding foam. Although I allowed the foam to expand naturally, its growth was ultimately constrained by the predetermined skeleton I had created with the chicken wire. This represents a transitional phase where I permitted some material autonomy, but still within strictly defined boundaries.

The colouration process for this work involved extensive use of an airbrush, with colours that were carefully calculated and precisely applied. Despite allowing some material behaviours to manifest, my approach remained predominantly one of control—the expanding foam could only grow where I permitted it to, and the colours were entirely dictated by my design decisions.

The work maintained a rectangular composition, demonstrating that despite material experimentation, I remained conceptually tethered to traditional painting frameworks.

- “The Labyrinth”: Confined Flow

2024

60x60x0.4cm

Acrylic Sheet and Epoxy Resin

“The Labyrinth” from my first unit of recent work marked another step in my evolution. In this piece, I allowed epoxy resin to flow within pre-carved grooves in acrylic boards. While this represented increased material freedom compared to my earlier works, the resin remained limited to flowing within paths I had predetermined. The entire composition was still confined within a precisely cut acrylic frame, maintaining the rectangular format characteristic of traditional painting.

This work illustrates a halfway point in my journey—I was beginning to appreciate material properties and behaviour, but still imposing significant constraints on how those properties could manifest. The resin had limited agency, permitted to flow and interact only within the boundaries I had established.

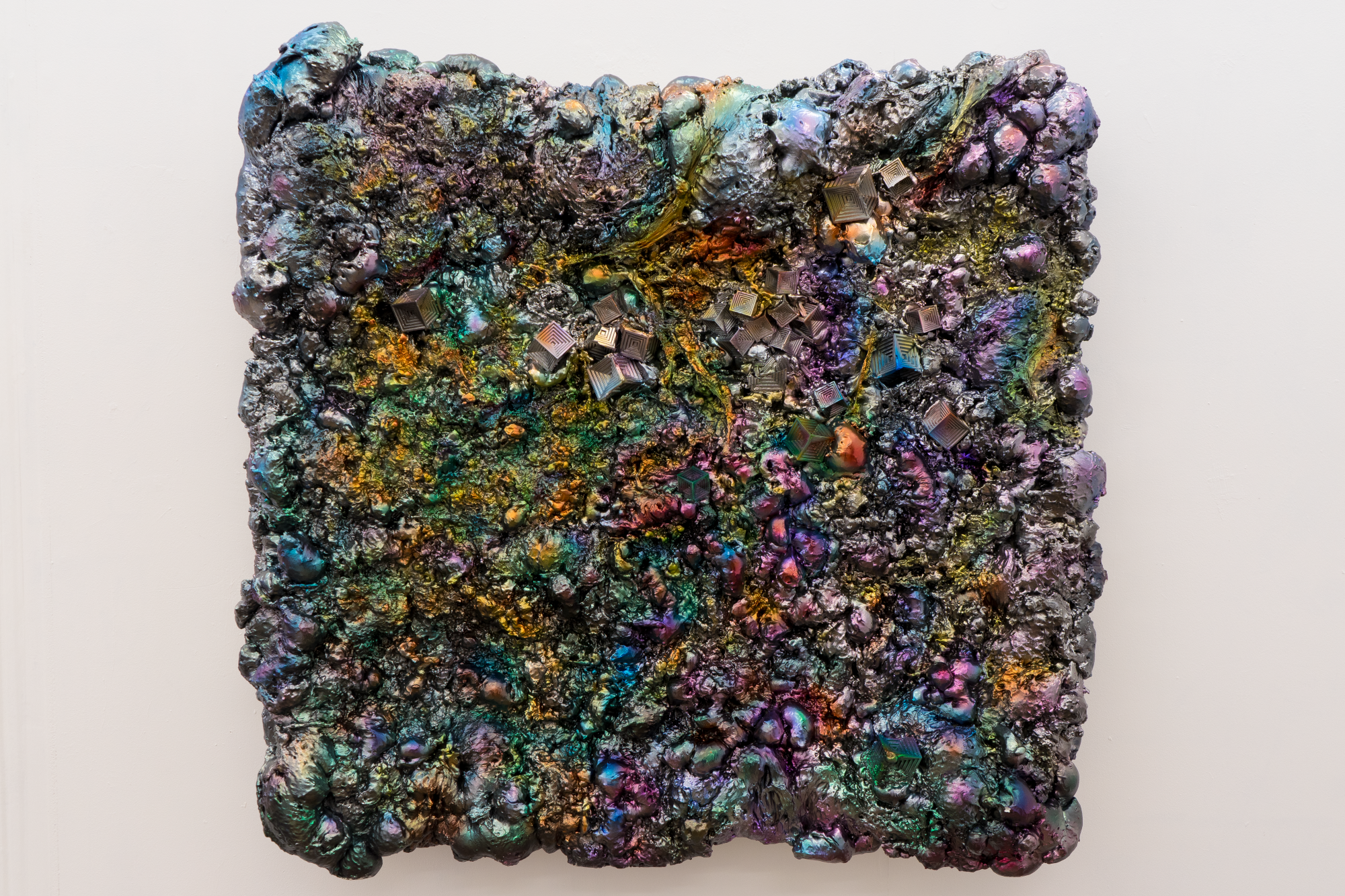

- “Crystal Interweave”: Breaking Free.

2025

50x30cm

Epoxy resin and Mylar film.

My latest piece, “Crystal Interweave” from my Unit 2, is a total breakthrough from these restrictions. I stopped using plans completely, and let the materials do their own thing, and find their own forms and spaces. The artwork emerges from the wall in an organic manner and is not tied to rectangular shapes or compositional methods.

My understanding of material agency—no longer about imposing my will on passive substances, but instead participating in a dialogue with materials through their properties and behaviours is embodied in this piece. The forms arise from the materials themselves, rather than from preconceived designs, thus producing results that could not otherwise be achieved through rigid control.

Evaluating Success and Challenges.

The success of this evolution lies in the rich visual and conceptual possibilities that have emerged from the embrace of material agents.

The work named “Crystal Interweave” establishes an active dynamic with its environment that my previous, more controlled works did not. The free-form shapes of the piece provide a better integration with architecture, so that it appears to be growing out of or coming from the architecture.

The intervention had led to discoveries not identifiable by planned experimentation, of which epoxy resin’s unique approach with various surfaces and environmental conditions is an example. For example, epoxy resin interacts uniquely with different surfaces and conditions in the environment. The different environment, different lighting, and different background all make it different.

However, challenges remain. Working collaboratively with materials requires relinquishing a degree of predictability and control, increasing the risk of “failure” by conventional standards. Often, limitations of materials like epoxy resin have to do with their technical properties (working time, toxicity, and environmental impact). Additionally, as these works move further from traditional painting formats, questions of display and conservation become increasingly complex.

An analysis of key works indicates that there has not just been a technical evolution but a fundamental reconceptualisation of my practice.

The journey from canvas constraints to material freedom represents a fundamental reconceptualisation of my relationship with materials and the creative process. By embracing materials as collaborators rather than subordinates, I’ve discovered possibilities inaccessible within traditional frameworks, opening new territories for exploration in my practice.

V. Future Directions: Expanding Scale and Deepening Concepts

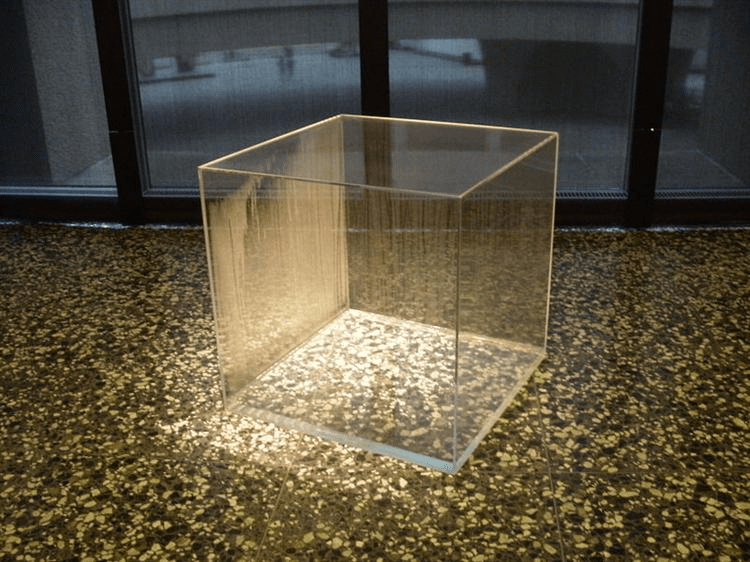

As I contemplate my artistic trajectory, Hans Haacke’s “Condensation Cube” (1963-65) provides a compelling framework for evolving my exploration of material agency. This pioneering work—a transparent acrylic cube containing water that continuously undergoes condensation and precipitation—demonstrates an approach that transcends traditional artistic control.

Condensation Cube, 1963-1965

Plexiglas and water

76 x 76 x 76 cm

Haacke’s Influence: Systems and Material Phenomena

Haacke’s piece fundamentally challenges the relationship between artist and material. Rather than imposing form onto substances, he created conditions for natural processes to manifest autonomously. As he stated in his 1965 manifesto, “…make something which experiences, reacts to its environment, changes, is nonstable… …make something indeterminate, that always looks different, the shape of which cannot be predicted precisely…” (Haacke, 1965).

Comparing our approaches reveals instructive differences. My work with epoxy resin still involves significant decision-making about placement, colour, and composition, even as I allow materials some freedom. Haacke’s work, in contrast, establishes initial conditions and then surrenders entirely to physical laws. The water’s movement occurs without his direction, making visible the otherwise invisible forces of thermodynamics.

What I’ve learned from Haacke is the power of restraint and the conceptual depth that can emerge from embracing natural phenomena as artistic content. This suggests my future works might benefit from further reducing direct manipulation, instead creating conditions for material interactions to unfold with greater autonomy.

Moving Beyond Painting Mentality

This shift needs a new vocabulary based on “systems,” “processes,” and “emergent properties” instead of “images” or “representations.” As Jack Burnham wrote, “We are now in transition from an object-oriented to a systems-oriented culture. Here, change emanates not from things, but from the way things are done” (Burnham, 1968, p. 31). This means creating works that show what materials do rather than just how they look.

Expanding Scale: Challenges and Possibilities

Scaling up presents exciting possibilities and significant challenges. Larger works could create more immersive experiences, changing the viewer’s relationship with the work from just looking to participating.

Technical challenges include safely handling larger quantities of potentially harmful materials, developing appropriate supports, and transporting non-rectangular forms. Despite these challenges, larger-scale work would allow environmental factors like air currents and temperature variations to have stronger effects on material behaviours, creating better connections with Haacke’s systems-based approach.

Enhancing Visual and Sensory Impact

Future works can strengthen their impact by engaging multiple perceptual modalities beyond the visual, including acoustic and haptic properties. Drawing from Haacke’s example, I might create pieces that transform noticeably over time, encouraging repeated viewings and revealing different aspects of material behaviour throughout exhibition periods.

Deepening Conceptual Frameworks

To transcend purely visual appeal, my work needs stronger conceptual underpinnings connecting material phenomena to broader philosophical or environmental concerns. Haacke’s work functions powerfully as a metaphor for larger ecological and social systems.

Moving forward, I envision works that not only showcase material properties but also use those properties to prompt reflection on our embedded position within material systems.

Making art like Haacke’s “Condensation Cube,” my future works may combine sensory experience with conceptual insight. In other words, I will use material phenomena to illuminate aspects of existence that we often don’t see, or recreate material phenomena that we can see every day.

VI. Conclusion

This critical reflection traces my artistic evolution from controller to material collaborator. Through exploring the agency of materials like epoxy resin, I’ve moved beyond traditional rectangular frameworks and precise control toward more organic, collaborative creation. Drawing on Ingold’s theoretical framework and inspiration from artists like Haacke, I’ve repositioned my artistic identity, discovering richer creative possibilities by allowing materials to be active participants rather than passive vehicles. This transformation has enhanced my work’s environmental integration and conceptual depth while presenting new challenges. Moving forward, I aim to further reduce direct manipulation, creating systems where material phenomena can unfold with greater autonomy.

Bibliography

Ingold, T. (2010) ‘The textility of making’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34(1), pp. 91-102.

Burnham, J. (1968) ‘Systems Esthetics’, Artforum, 7(1), pp. 30-35.

Riley, B. (1966) *Over* [Emulsion on board]. National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Haacke, H. (1963-1965) *Condensation Cube* [Plexiglas and water]. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.n, D.C.